U.S. stocks fell sharply, after markets recorded heavy declines in Asia and Europe.

A wave of panic rippled through financial markets on Monday, with stocks falling sharply in the United States and around the world as investors zeroed in on signs of a slowing American economy.

Monday’s drop extended a sell-off that had begun last week, after the U.S. jobs report on Friday that showed significantly slower hiring, with unemployment rising to its highest level in nearly three years. This deepened fears that the world’s largest economy could be sliding into a recession and that the Federal Reserve may have waited too long to cut interest rates.

The drop was exacerbated by other factors — concerns that technology stocks had run up too far too fast, and that a suddenly strengthening yen would hurt the prospects of Japanese companies and some global traders — both hit markets too.

U.S. markets. The S&P 500 fell about 3.7 percent in early trading. The technology heavy Nasdaq composite dropped 4.7 percent. “Markets are a little bit out of control,” said Andrew Brenner, head of international fixed income at National Alliance Securities. “This is just total panic. It’s not real but it is painful and it could be with us for a few weeks.”

Japanese markets. The Nikkei 225 index dropped 12.4 percent, its biggest one-day point decline, larger than the plunge during the Black Monday crash in October 1987.

European markets. The Pan-European Stoxx index fell about 3 percent, with every major market on the continent recording declines.

Fed rates. Based on the weakness in the U.S. jobs report, Goldman Sachs said in a note that it now expected the Fed to cut rates at its next three meetings — in September, November and December — a more aggressive timetable for cuts than the investment bank had previously expected. At their meeting last week, Fed officials held interest rates at a two-decade high, where they have remained for a year.

U.S. recession. Analysts at Goldman raised their forecast for the probability of a U.S. recession in the next 12 months to 25 percent, up from 15 percent.

Apple shares fell more than 5 percent on Monday after Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway reported that it had sold nearly half its stake in the tech giant. Berkshire first invested in Apple in 2016 and accumulated a nearly 6 percent stake that was worth more than $150 billion. Over the past eight years, Apple’s stock has risen or fallen based on whether or not Berkshire bought or sold shares of the company.

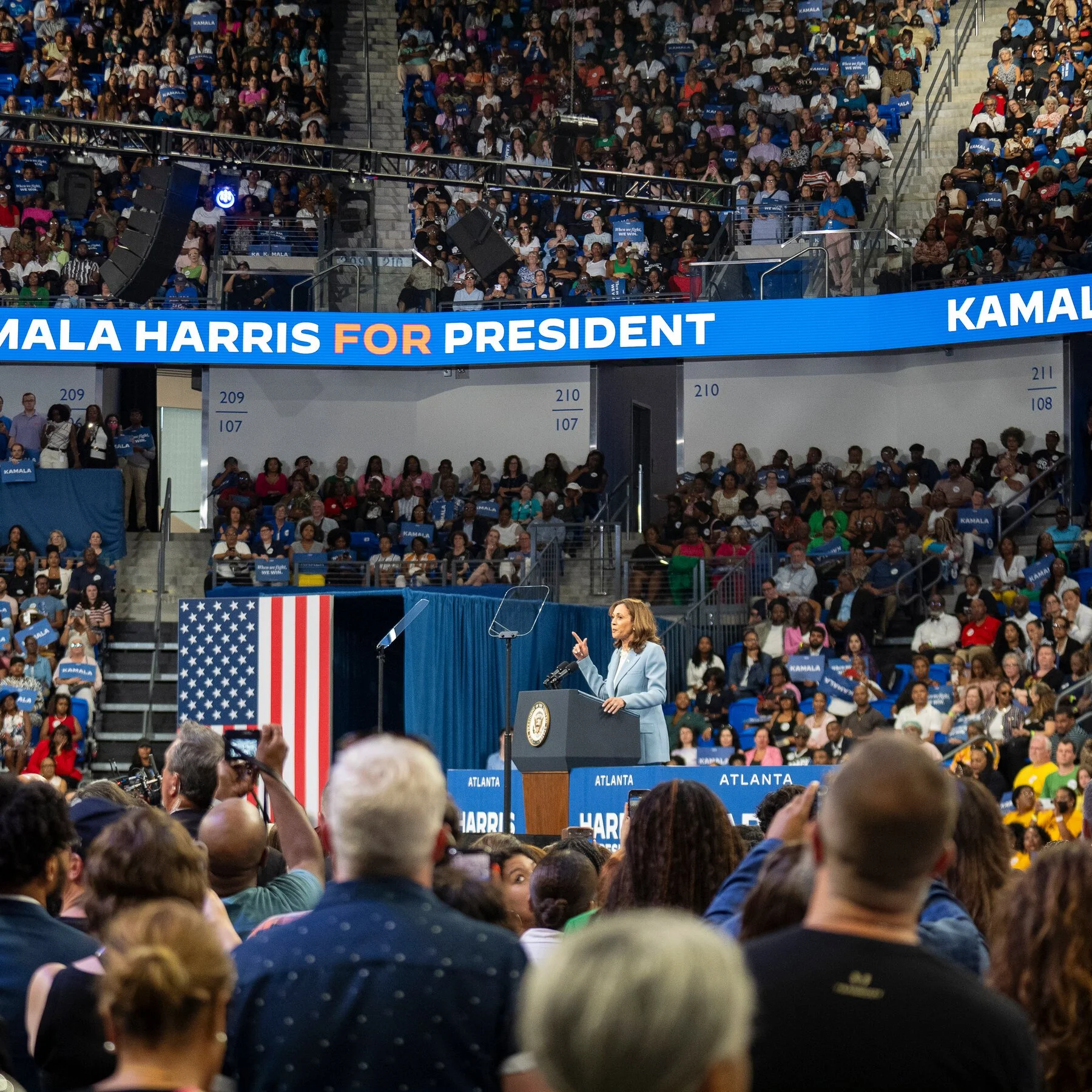

While Trump is talking up the “Kamala Crash” today, he was taking a much different approach in February 2020 when the the stock market crashed on his watch due to pandemic fears. At that time, his advisers urged investors to “buy the dip,” and he suggested on social media, “Stock Market starting to look very good to me!”

The prices of Bitcoin and other major cryptocurrencies plunged over the last two days, mirroring the volatility in global stock markets and ending a run of growth and excitement in the crypto industry.

Bitcoin’s price has dropped about 12 percent since Sunday, falling to roughly $53,000. The price of Ether, the second most valuable cryptocurrency, was down nearly 20 percent over the same period.

The precipitous falls show that digital currencies, once envisioned as an alternate asset class that would be shielded from gyrations in the world economy, remain vulnerable to the same broader economic forces that affect technology stocks and risky investments. And the panic is a reminder that Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are highly volatile, prone to dramatic increases and decreases in value.

Just a few days ago, the crypto industry was flying high. In January, the approval of a new financial product tied to the price of Bitcoin prompted a market surge that propelled Bitcoin to its highest-ever price. The excitement even led to a wave of new memecoins, the digital currencies tied to internet jokes.

That enthusiasm came to an end on Sunday, as global markets plunged. The panic was caused by several factors, including a slowdown in U.S. job creation and concerns that tech stocks had increased too quickly.

As the price of Bitcoin cratered, investors shared despondent memes on X, while industry leaders tried to reassure crypto fans that the market would rebound.

“Yikes,” Cameron Winklevoss, one of the founders of the crypto exchange Gemini, wrote on X on Sunday. And then a few minutes later: “Everything is fine.”

Many economists had the impression that a correction was in the cards, said Klaus-Jürgen Gern, a researcher with the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. “Various factors are coming together in a way that is triggering very strong reactions,” he said. “I do believe that a correction is now taking place.”

”The danger is that some of the fears that may have triggered this slide coincide with this considerable increase in tension in the Middle East, which then also raises concerns about a new external shock that could then hit the global economy as a whole,” he added.

It’s especially wild given the relative recency of that negative data. Employment growth was surprisingly robust up until July. The relatively weak report last month — 114,000 jobs and a jump in the unemployment rate to 4.3 percent — contained some indications that tumultuous weather might have been at play.

Meanwhile, rate cut chatter has already been pulling mortgage interest rates down. Freddie Mac reported last week that mortgage rates — which began their rise to over 7 percent in late 2021 — fell to the lowest level since this past February.

Advice: When the stock market drops, stay calm and do nothing.

The markets are in turmoil, but you know what you’re supposed to do now, right? Let’s all take a deep breath, tie our hands behind our backs and say it together: We will not sell stocks in a panic. We will, in fact, do nothing at all right now.

Many of the people who are trading today are professional investors of various sorts. Here’s a dirty little secret about, say, hedge funds: All of their trading in reaction to world events doesn’t lead most of them to do better than sticking their money in an index fund that tracks the stock market. Mutual fund managers don’t do much better.