RFK jr. vs Musk: How GLP-1s will disrupt the economy in the new year

Weight loss drugs are saving lives, shrinking waistlines and shaking up the economy.

A new technology is disrupting the economy. Even experts don’t entirely understand how it works, its full range of uses and what its unintended consequences could be.

No, it’s not artificial intelligence; I’m talking about weight-loss drugs. With adult obesity rates falling last year for the first time in more than a decade, drugs such as Ozempic and Zepbound are already reshaping Americans’ waistlines. Now, they’re poised to reshape the entire economy, too.

As of May, roughly 1 in 8 American adults have tried GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1s for short). This percentage has almost certainly grown since then, as telehealth companies, “medi-spas” and compounding pharmacies aggressively market GLP-1 prescriptions.

We’re only just beginning to learn the full universe of effects for this class of drugs. Originally developed to treat Type 2 diabetes, GLP-1s were soon discovered to be effective in treating obesity and managing weight loss. Now there’s an ever-growing list of other potential uses (on- or off-label), including for treating heart disease, sleep apnea, Alzheimer’s, substance abuse and maybe even gambling addiction.

“I’m on Wegovy for the rest of my life, but I can show you an entire medicine cabinet full of medications that I no longer have to take,” said Taryn Mitchell, 53, a GLP-1 patient in Greensboro, North Carolina.

So here are seven reasons these blockbuster drugs will disrupt the U.S. economy in 2025 — and beyond.

1. Spending on GLP-1s is skyrocketing.

Most insurance plans don’t (yet) cover GLP-1s for weight loss, and the list price for the brand-names can run upward of $1,000 a month. But, that hasn’t scared everyone off: Pharmacies are having trouble keeping the meds in stock, and semaglutide (the active ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy) was the top-selling drug in 2023.

Perhaps this is unsurprising, given that more than 40 percent of Americans are clinically obese. The United States spent an estimated $40 billion on all GLP-1 meds in 2024, with spending projected to triple by 2030.

2. Consumers are spending less on food and alcohol.

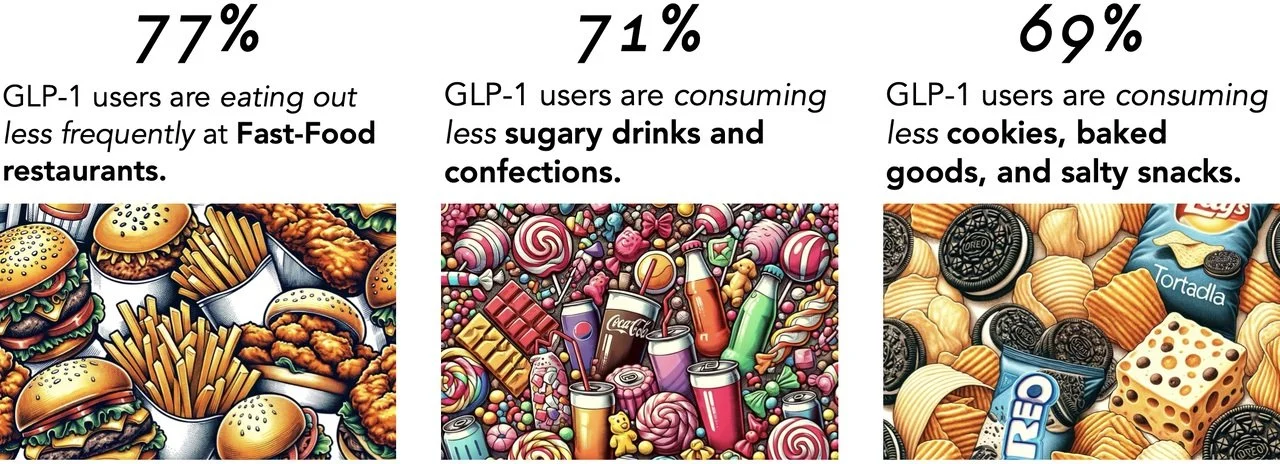

Some junk-food companies and alcohol sellers are freaking out about the prospect of reduced appetites or booze cravings. As they should: The average household with at least one family member on a GLP-1 is spending about 6 percent less on groceries each month within six months of adoption. That translates to about a $416 reduction in food and drink purchases per household a year. Spending reductions are even greater for high-income households, according to a new study by researchers at Cornell University and Numerator.

Some categories have been hit harder than others. For example, these households are spending about 11 percent less on chips and other savory snacks and 9 percent less on sweet bakery items. Select healthier foods, such as fresh fruits and yogurts, have gotten a very tiny bump.

Companies are scrambling to adapt by offering new product lines specifically tailored to GLP-1 customers, with limited success.

3. Other consumer-facing industries are being transformed, too.

There are some potential retail winners. For example, rapid weight loss has encouraged some patients to replace their wardrobes. The clothing rental company Rent the Runway recently reported that more customers are switching to smaller sizes than at any time in the past 15 years.

Airlines could save significant money on fuel if passengers slim down en masse, a financial firm projected. Life insurers could cash in, too, given the many mortality risks linked with chronic obesity. “Generally, running a life insurance company right before immortality is discovered — cancer vaccines, antiaging therapeutics — is a good business to be in!” said Zac Townsend, CEO of the life insurance company Meanwhile.

Nearly every GLP-1 user I’ve interviewed in the past year has also mentioned spending money on new hobbies, such as pottery classes or pickleball leagues. Some deliberately picked activities to replace social engagements that revolve around food or alcohol; others said they simply gained the energy and self-confidence to try new things.

“I am way more active than I have been,” said Mitchell, whom I interviewed for a recent PBS NewsHour story about Ozempic economics. “I took my daughters horseback riding on the beach last Christmas. We’ve been snow tubing, things that I would have never thought to do.”

4. Drug spending is distorting global financial markets.

The Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, maker of Ozempic and Wegovy, nearly single-handedly kept its home country’s economy out of recession last year while most of Europe struggled. And because Americans are the primary customers of these meds, U.S. dollars flowed heavily into Denmark, causing the Danish krone to strengthen relative to other currencies.

To keep the krone’s value steady relative to the euro, the Danish central bank had to cut interest rates. Put another way: Overweight Americans unintentionally helped Danes get cheaper mortgages.

5. Governments and private insurers are buckling under the cost of these meds …

Again, GLP-1s are extremely expensive. Some states and private insurers that previously covered GLP-1s for weight loss reversed course because they risked going broke.

Recently, the Biden administration proposed requiring Medicare and Medicaid to cover these meds as a treatment for obesity as a chronic disease. This would cost Medicare alone an additional $35 billion between 2026 and 2034, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

6. … but they could ultimately save tons of money on other health spending.

Obesity is a chronic disease associated with dozens of other ailments, including joint problems and cancers. So helping Americans lose weight has the potential to make the public much healthier — and reduce spending on other (costly) care.

Seven women in Mitchell’s family, for instance, had breast cancer and both of her parents developed forms of dementia. Mitchell herself developed diabetes, too. All of these problems have linkages with obesity. “I don’t want to be sick,” said Mitchell, explaining why she turned to Wegovy after previously trying diets, exercise, therapy and surgery. “After taking care of my parents, I said, ‘I don’t want my children to have to take care of me.’” Her obesity is now in remission and she no longer has diabetes.

Of course, such potential health benefits — and cost savings — will materialize more broadly only if patients keep up with their medications and adopt healthier habits to help maintain lower weights. Which is a big if.

Research suggests most patients who were prescribed these meds stop taking them within a year. Some stop because they’ve successfully reached their goal weight. But many others report stopping because of costs, unpleasant side effects, drug shortages or squeamishness about needles.

7. The labor market could get a boost.

Besides robbing many Americans of their energy, health and self-esteem, obesity has also robbed the U.S. economy of some of its most precious assets: workers.

Obesity-related disabilities, absenteeism, “presenteeism” (that is, showing up but not performing your best) and premature death all have enormous social and economic costs. Which means that making Americans healthier can make the labor market healthier, too, especially if interventions occur while patients are young and have many working years left. Mitchell, for instance, said she picked up a second job this summer, something she would not have had the energy to do before her recent 85-pound weight loss.

These drugs don’t yet “pay for themselves,” but if the list price gets cut in half, they would likely start to — at least, if you add up all the workforce benefits, quality of life improvements and reduced spending on other care.

Innovation, competition and expanded production capacity are already stoking a price war among drugmakers. Medicare officials are also expected to start negotiating the prices of these drugs, potentially reducing the blow to federal budgets and helping private insurers’ bargaining positions as well.

That kind of payoff is a longer-term goal, not one we’d likely see in 2025. But it’s a reason to celebrate as we ring in the new year, nonetheless.