How Trump Rewired the Electoral Map

Charlie Mahtesian is POLITICO’s senior politics editor. Illustration by Yoshi Sodeoka

15-18 minutes

When President Barack Obama launched his 2012 reelection campaign, he did it with back-to-back rallies in a pair of logical places: Virginia and Ohio. The two essential swing states, with 31 electoral votes between them, were vital to Obama’s chances of winning a second term.

Ohio, a traditional Midwestern bellwether, epitomized the old electoral map, from the now-distant era when presidential elections featured dozens of contested states and candidates sought to campaign in all of them. Virginia, a Southern state that for decades had voted Republican for president until Obama broke the streak in 2008, represented a new map, one in which rapid demographic change created new opportunities for Democrats. Together, they were emblematic of the Electoral College map Obama and his diverse coalition rewired in 2008 to win the White House.

Just eight years later, though, no one is talking about Ohio and Virginia as critical battleground states. When Democrats point to a Rust Belt path to the presidency in 2020, they are referring to Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Ohio—along with Florida, the pivotal battleground state in recent elections—is not part of the conversation. For the most part, both sides view it as one shade short of a red state.

Virginia—for decades part of the Republican Party’s solid South—now gets the silent treatment as well. Once regarded as unreachable by the Democrats, now it’s broken so hard toward their camp that its brief reign as a swing state may already be over.

This is the Electoral College on Donald Trump.

Familiar presidential battlegrounds—not just Ohio and Virginia, but also Colorado, Iowa and more—are fading from the radar. States that haven’t experienced a top-of-the-ticket dogfight in decades—like Arizona, Georgia, Minnesota and maybe even Texas—are suddenly poised to play a pivotal role.

You can argue about whether Minnesota—a cradle of liberalism that produced Hubert Humphrey, Walter Mondale and Paul Wellstone—is a pipe dream for Trump in 2020. Or whether Texas—where Republicans hold all nine statewide elected offices, both Senate seats and both chambers of the Legislature—will truly be in play in November. But one thing seems increasingly inarguable: This presidential race will be fought on electoral terrain that would have been unthinkable four years ago, before Trump blew everything up.

That’s clear from the polling that’s being conducted by the parties and independent groups, from the battleground-state forecasts issued by political handicappers and major news organizations, and the early allocation of resources from the parties, campaigns and other interested entities. And it’s very much on the mind of campaign strategists who, in conversations, acknowledge the reconstituted map and the unique challenges it presents for both sides.

It’s something short of a historic realignment, but more than just a hiccup. Trump has thrown the battleground state map into flux, and punctured long-held shibboleths about the potential paths to the White House.

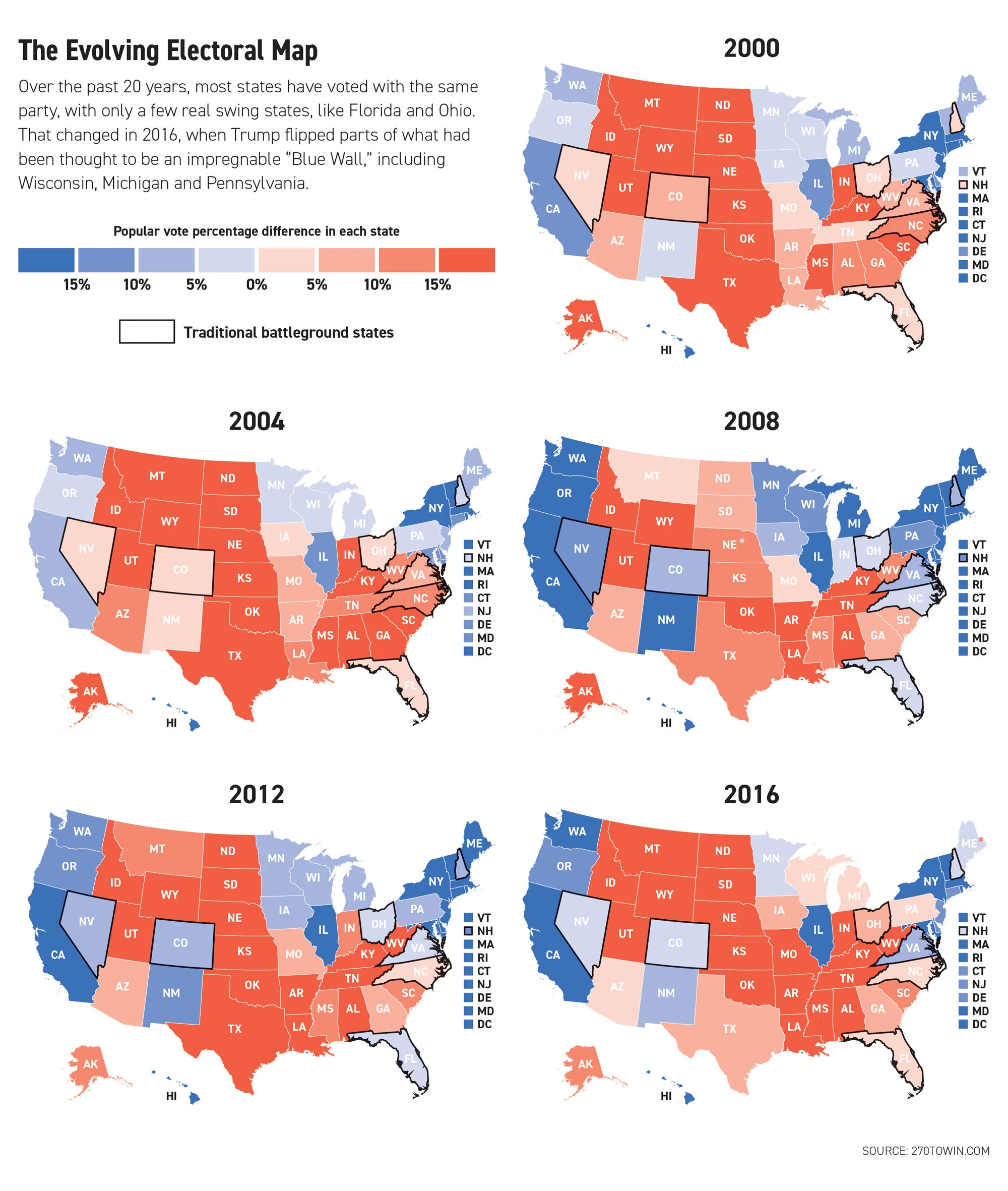

The pre-Trump electoral map was fairly static. For five consecutive elections, from 1996 to 2012, the nation had been locked into World War I-style presidential trench warfare, with 37 of the 50 states voting for the same party at the presidential level.

That elevated a relatively small universe of core battleground states that were within reach for either party—typically eight to 10. For roughly a generation, the most consistent members of this group of states have been Colorado, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio and Virginia. While there were other competitive states—among them Iowa and Pennsylvania—that warranted some level of care and feeding, these seven were the closest and most hard-fought. Of the last 28 presidential elections in those states, 27 were decided by single digits.

In 2008, Obama won every one of those states. In 2016, Trump lost a majority of them.

But Trump still won the two biggest, Florida and Ohio, and he also pulled off a feat almost no one predicted: He flipped Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, a 46-electoral vote trio that hadn’t voted Republican—individually, much less together—for president since the 1980s.

With that feat, Trump shattered the presidential map we’ve grown accustomed to. The most immediate consequence was to blow up the idea of a “Blue Wall,” a term applied to a northern tier of 18 states, stretching from coast to coast, that appeared to provide a structural advantage for a Democratic nominee. Going into the election, it seemed almost unbreachable, which was a key factor driving the belief that Hillary Clinton was on a glide path to the presidency.

Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin were part of its foundation—but so was Minnesota, which Hillary Clinton won by just 45,000 votes after nearly a half-century of Democratic top-of-ticket dominance. Even Walter Mondale—who was also a native son—won Minnesota in Reagan’s 49-state 1984 reelection landslide. Despite that history as a blue state lodestar, Trump nearly pulled off a victory there that would have been the shocker of a shock election. His stunning near-miss—he fell short by just 1.5 percentage points despite spending limited money and attention there—has placed it high on the Trump reelection campaign wish list.

While the state’s demographics aren’t quite as favorable to Trump as those in several other nearby states, his campaign has already said it’s planning to pour up to $30 million into the state. That’s roughly 1000 times what it spent there in 2016. To show his resolve, the president has also visited the state a handful of times since capturing the White House.

In all of those Midwestern states, Trump assembled something like a reverse Obama coalition, marked by squeezing ever higher percentages and turnout from a shrinking white electorate. And he created a dilemma for Democrats over which path to pursue in the future: Focus on a map that prioritized the Obama coalition of young people, women and nonwhite voters, or double back to a more traditional map that prioritized winning the white working class.

The idea that Ohio might not be at the center of the presidential election universe seems preposterous at first. But Trump’s 8-point win in 2016 represented the widest GOP winning margin in a generation. Two years later, in what was nationally a great Democratic year, Ohio Republicans won every statewide executive office.

Billionaire Democratic candidate Tom Steyer publicly acknowledged what many in his party think privately during an October campaign stop in Columbus.

“You guys live in a red state,” he said. “I know people call it purple, but it’s pretty darn red.”

The key in Ohio, as in Iowa—another traditionally competitive state that doesn’t figure to be a core battleground this year—is the population of non-college educated whites, Trump’s demographic sweet spot. In Ohio, they made up 55 percent of the vote in 2016 and Trump won 63 percent of their vote, according to research by Ruy Teixeira and John Halpin for the Center for American Progress. In Iowa, non-college educated whites were 62 percent of voters and they delivered 57 percent of their ballots to Trump. At those levels, Trump can sustain some falloff in 2020 and still have a considerable advantage—a calculus that is likely to strip both states of their treasured designation as swing states.

Yet just as Trump created a dilemma for Democrats, he also created one for himself—and for future GOP nominees. His brand of populism and white grievance politics amped up rural turnout in key states, particularly in key Midwestern states where white, non-college voters cast more than half the vote in 2016. While that enabled Trump to pick off five states that Obama carried twice, it also planted an Electoral College time bomb, set to detonate after he leaves office. The president has tethered the party’s future to a shrinking population while at the same time accelerating the crack-up of the GOP’s suburban base and alienating Hispanic and minority voters in many states where the nonwhite share of the vote is growing.

These shifts are already shaping the contours of Trump’s reelection map. Virginia and Colorado—two states with significant populations of white, college educated voters and nonwhite voters—offer a look into that possible future. The Republican Party’s standing in the two states has nosedived in recent years, leaving both under near-complete Democratic control.

Similar demographic forces are combining to turn longtime red states Arizona and Georgia—neither of which has been a core battleground state before—into two of the most competitive in 2020. Arizona has voted Democratic just once in 70 years; Georgia just once in the past 36 years. At best, in recent elections they’ve been viewed as so-called “stretch” states that might come through for Democrats only if the stars aligned. Some Democrats still seethe over the Clinton campaign’s late campaign foray in 2016 into both states, convinced it was an epic blunder that distracted the campaign from the unfolding crisis in Wisconsin.

This year, though, no one questions the strategic relevance of Arizona and Georgia. Arizona is expected to be so tight that it’s listed by most political handicappers as a toss-up. Major news organizations, including CNN and the New York Times, now include it in their battleground state polling for the first time.

Georgia is a heavier lift for Democrats. As recently as 2012, Georgia rated as one of 19 states considered so irrelevant at the presidential level that they were dropped from the roster of exit polls that year. What was the point of polling states where the outcome was all but predetermined?

But the past four years have exposed the rot in the GOP’s grip on the state. Trump got plastered in the traditionally Republican suburbs of Atlanta in 2016, en route to winning a bare 50 percent of the statewide vote. Two years later, Democrat Stacy Abrams revealed a potential path to victory, by expanding the electorate through voter registration and a focus on African American turnout, and came within 55,000 votes of winning the governorship.

Then there is Texas. Democrats have long predicted the state’s changing demographics would lead to an inevitable transition from red to blue. Howard Dean was so sure of it that in his 2009 farewell speech as DNC chairman he said he could “guarantee” that Texas would vote for Obama in 2012. Obama, of course, didn’t come close. He lost Texas that year by 16 points. But in 2016, Trump ran well behind Mitt Romney’s pace, largely due to white collar suburban defections from the GOP. Two years later, Beto O’Rourke nearly pulled off a massive upset over Sen. Ted Cruz, a performance that sent shudders through the Texas GOP establishment.

In a secretly recorded audio released last year, the state’s House Speaker, Dennis Bonnen, conceded as much, saying Trump is “killing us in the urban-suburban districts.”

Texas still figures to be a reach for Democrats in 2020. But a spike in Latino turnout—or an increase in Latino support for the Democratic nominee—sparked by Trump’s immigration policies could well change that. At the very least, thanks to the president Texas is likely to command more investment of campaign resources, and candidate face time, than it has seen in decades.

Even the electoral freak shows in Maine and Nebraska—the two states that award electoral votes by congressional district, in addition to the overall state winner—are likely to be center stage in 2020. In November, Trump’s unique demographic appeal might win him the single electoral vote attached to Maine’s rural-based 2nd District once again. But it might come at the cost of the single electoral vote attached to Nebraska’s urban and suburban-based 2nd District, where Trump generates more revulsion.

None of this is to suggest Trump has sparked the kind of tectonic changes envisioned in 1969’s The Emerging Republican Majority, a classic of the political realignment genre that predicted the end of the New Deal coalition and the rise of a new conservative one. The president’s political goals are far more narcissistic. His strategies are far too zero sum.

Unlike past presidential strategists who envisioned creating historic party coalitions that would reorder the electoral map for generations—as Karl Rove once did after George W. Bush’s reelection in 2004, which Rove compared to the 1896 realignment ushered in by William McKinley—Trump’s campaign manager, Brad Parscale, imagines a different future.

In a September speech designed to bolster the resolve of the sick man of American politics, California’s sad-sack Republican Party, Parscale laid out a vision that transcended the notion of swing states, political maps and demographic trends. It wasn’t rooted in fanciful notions of partisan realignment. Rather, it was pegged to the family of a singular candidate, Donald Trump, and the style and values he espouses. In that vision, party is subordinate to personality—a personality that has reshaped the electoral map.

“The Trumps will be a dynasty that will last for decades,” Parscale said, “propelling the Republican Party into a new party.”