Drownproofing

11-13 minutes

BY: CARSON VAUGHN

ILLUSTRATIONS: CHARLIE LAYTON

The sun was just beginning to set when the propeller snagged the towrope and the mosquitoes swarmed the idle runabout. Back at the houseboat, still tethered to the dock, the celebration was in full swing: cold drinks and fresh barbecue and so many toasts to the bride-to-be. Little did they know the groom had literally jumped ship; that he and his best friend, unwilling to endure another blood-sucking bite, had chosen to swim several hundred yards back to the party rather than wait for help; that they’d spent all afternoon swaddled in the Arkansas heat, skiing and boating and hamming it up, and were now foolishly racing to shore from the middle of the lake, several drinks deep.

“I just dove in with him,” says Ed Beard, IM 57. But of course, his friend was a competitive swimmer, and Beard was not, and roughly halfway back, “I just gave out.” His 23-year-old ego couldn’t propel him any further. His adrenaline was drained. He was cramping and beginning to panic.

“Johnny,” he sputtered. “I’m in trouble.”

His friend, a fellow Phi Delta Theta, circled back. He reminded Beard of their “drownproofing” course at Tech, and though Beard hadn’t passed every test, the term itself triggered his better instincts. He remembered all the hours he’d spent in that old campus pool, the rigorous training he and his peers had endured: the underwater obstacles, the pint-sized swim coach barking orders. He slowed his breathing, “got my mind settled down,” he says, and began to alternate between a back float and—when his strength returned—a slow front crawl, off and on, back and forth, swallowing one creeping doubt after the next, relaxing again whenever the cramps returned, until finally the houseboat was in reach.

“They were all partying and carrying on,” he says. “I don’t think I even said anything about it—but I never forgot it. I knew I was in trouble.”

Nearly 60 years later, after a career in investment banking, Beard noticed a discussion on the GT Swarm chat forum about drownproofing, a term he hadn’t heard in years. He posted a short note about his own harrowing experience on that lake near Pine Bluff, Arkansas, so long ago, and how “the GT drownproofing course…saved my life.”

“I did that mainly to give credit to [coach] Freddie Lanoue,” he says. " I may be here posting because of that course."

Born in Brockton, Massachusetts, in 1908, Frederic Richard Lanoue, a self-described “Spartan disciplinarian,” sparked a revolution in water safety. “Although his voice suggested a permanent cramp in mid-stream and his physique was more suitable for right guard than Australian crawl,” reported the Knoxville News Sentinel following one of his numerous speaking engagements in January 1954, “Fred was a surprising hit with the audience…And he was interesting, too.” He wore exclusively second-hand clothes and a gap-toothed smile, and though he barked orders like a drill sergeant, his hairline receding a little further each year, his students adored him.

“He was emphatic about every statement he made,” says Ed McBrayer, AE 68. “He was quick to tell you if you were doing something wrong, and rewarded you if you did something right.”

Though once a competitive swimmer, Lanoue himself was a natural “sinker,” he said, all muscle and bone. He couldn’t float—not without a great deal of effort, anyhow. And thus in 1938, as a young swimming instructor at the Atlanta Athletic Club, he began developing a system he called “drownproofing,” or “a new survival technique that can keep you afloat indefinitely,” he wrote in his popular 1963 book for Prentice Hall, the educational publisher—even his fellow sinkers. In its most basic sense, drownproofing is a method of controlled breathing that allows one to conserve energy while suspended in water, no matter the circumstance: wet clothes, body cramps, rough seas, and more. But while Lanoue’s instruction was often physically punishing, a fortified mental fitness was the ultimate goal.

“This technique is better and cheaper than any insurance or life-saving gadget a man can buy,” Lanoue once said. “What we’re trying to accomplish is a change from fear of water to respect for the water.”

When Tech opened its new swimming pool at the Heisman Gym in 1939, the college hired him as the head swim coach. With Lanoue at the helm, Tech would win four SEC championships within the next decade and change, and in 1958, he would be elected president of the College Swimming Coaches’ Association. But just one year after he arrived at Tech, he also began teaching a quarterly drownproofing course—what he would ultimately consider his crowning achievement—to everyone who enrolled at Tech. The course proved so popular, so obviously practical, that it remained in the school’s course catalog until 1986, decades after Lanoue had died and his successor, Coach Herb McAuley, EE 47, took the reins.

“It was intense, but I don’t remember anybody throwing shade at the course,” McBrayer says. “Everybody thought it was a great thing to learn, and they were very proud that they had been through it.”

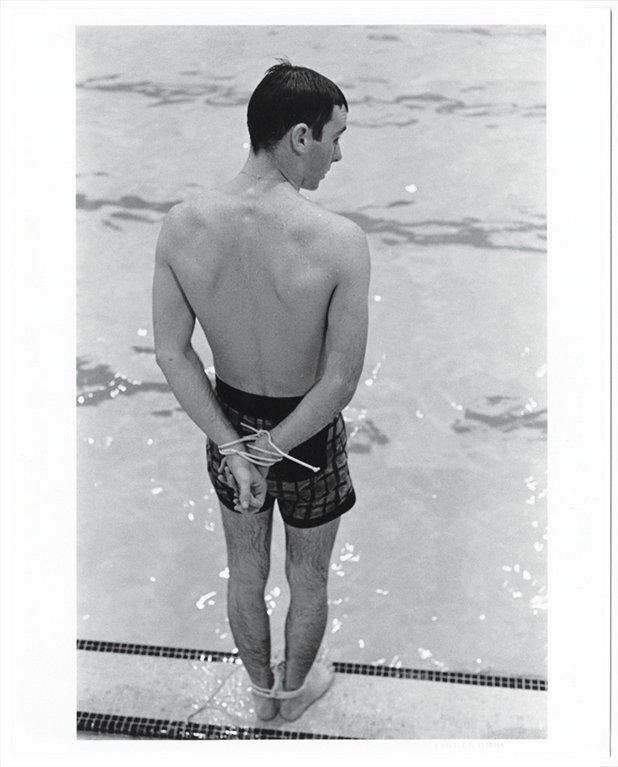

Tech students often spoke of drownproofing like a rite of passage, like boot camp—and for good reason. Lanoue’s primary objective was to keep his students above water in the event of an emergency, but he didn’t stop with a simple bob alone. Each course grew increasingly more difficult. Students eventually found themselves lashed to a 10-pound weight, sinking to the bottom of the deep end with their hands and feet tied together, tasked with staying afloat for a minimum of one hour. In perhaps the most extreme exercise, students were instructed to jump feet first off the diving board, push off the bottom, and swim the entire length of the 25-yard pool. And then back again. Underwater. Lanoue developed the test to simulate a particularly extreme boating accident in which one might need to swim out from beneath a flaming oil slick.

McBrayer still remembers the euphoria that washed through him just before he passed out—so eerily similar to the way Lanoue had once described it. He made it all the way down, and halfway back, the pressure mounting with every kick, every stroke, his blurry peers hovering poolside, and when his heart finally threatened to punch straight through, he felt a sudden, uncanny relief.

“I started feeling like I don’t really care if I go up or not,” he says. “And the next thing I knew I was gagging and coughing on the side of the pool, and two guys had me by the arm.”

McBrayer was one of just two out of the 20 students in his class to earn an ‘A’ that quarter, but Lanoue successfully taught thousands the basic tenets of drownproofing during his nearly 25 years at Tech. In fact, in 1954, he reported the following results in an article written for the Water Safety Congress and syndicated in papers throughout the country: Of the 4,000 Tech students who had completed the course, 3,800 could swim a mile “unclad;” 3,600 could swim a mile fully clothed; 3,200 could tread water for 45 minutes with their hands tied behind their backs; 2,500 could recover a body from a depth of 11 feet and tow it another 60 yards; and all of them could swim before graduation.

But Lanoue didn’t save his drownproofing course for Tech students alone. He also taught Naval Cadets and Peace Corps volunteers as a “water safety consultant,” and was hired to conduct private and public drownproofing seminars across the country. According to the UPI, both the British Royal Family and President Kennedy took great interest in his work, and the diminutive coach became so locally adored that Celestine Sibley, the celebrated Atlanta Constitution columnist, called it the “Fred Lanoue cult.”

“In Atlanta, there is a sizable community of citizens who think that the Georgia Tech swimming coach, Fred R. Lanoue, is the greatest man in the world,” she wrote in a June 1963 review of his book, Drownproofing: A New Technique for Water Safety. “They speak of his genius, his tough-fibered intelligence, his patience, his imagination.”

Sibley then praised the book herself, calling it “a fascinating revelation of how much research and study is going on locally in water safety.” Drownproofing reached thousands beyond the Heisman Gym, as did the serialized version later published in The Atlanta Constitution. But it was never quite enough—not for Lanoue. He often reminded his audience that roughly 7,000 Americans drown ever year, and claimed that at least 6,500 could survive by practicing his drownproofing technique. And so the “Spartan disciplinarian” kept at it, spreading the gospel of water safety wherever and whenever he could: to Mobil Oil Company employees in Lafayette, to children with physical disabilities at Georgia’s Warm Springs Foundation, and on the very day he died, to the Marines stationed at Parris Island in South Carolina.

Lanoue began lobbying for the Marines to implement his training program nearly a decade before, shortly after five soldiers drowned in a tidal stream during a controversial night maneuver. Almost a decade later, the notoriously tough outfit finally agreed. But Lanoue’s mission on the island was cut tragically short. On the first day of training, he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and was rushed to the naval hospital in Beaufort, where he soon passed away. He was just 57 years old, and left behind his wife, his two grown kids—a son in the Navy and a daughter in the Peace Corps—and a 12-year-old daughter, too, a future leader in the women’s self-defense movement and Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame inductee.

Tech no longer offers a drownproofing course, nor does the Navy teach Lanoue’s exact methods; it does, however, still require cadets and personnel to pass a series of related “swim qualifications.” But Lanoue’s legacy lives on, not just in the family he left behind, but in all the students who continue to heed the memory of his voice and utilize his time-honed techniques still today. Students like Ed Beard, who never quite perfected the bob but carried forever the cool head his instructor taught him—not a fear, but a respect for water that kept him alive when his body threatened to shut down. Students like Ed McBrayer, who now jumps at every opportunity to teach his friends and family the techniques Lanoue taught him. And every surviving member of the “Fred Lanoue cult” who still swears by the blunt and wise words of that balding and barrel-chested pitbull of a man.

“Never mind pretty little swimming pool situations. What is the worst situation you might run into from a swimming standpoint?” Lanoue once told a reporter at the Lexington Herald-Leader. “…Any ‘drownproofed’ person can handle this situation with ease. Can you?”